The Symbiosis of Science and Art

Discover the magical world where science and art intersect

by Caitlin Burke

https://www.art-mine.com

The history of the intersection between science and art, unlike any other history, has no beginning. On a macro scale, the closest approximation we have to the length of the relationship is the estimated age of the universe or 13.8 billion years. On a micro scale, we might assign the origin of life on earth as the demarcation. After all, the act of cell division is in many ways a kind of performance art – each cell moves in accordance with premeditated steps and is subject to the force of time, culminating in a beautiful ephemeral dance.

Tropfen (diptych), Volkmar Jesiek

For that matter, any interplay between definitive structures and chance represents the push and pull of art and science. The leaves on a tree branch are biologically and anatomically the same, but they grow to be different shapes, sizes, and colors. The universe, acting as artist, manipulates molecular structures like paint on a canvas, creating masterpieces as small as a strain of bacteria and as large as the planet Saturn. Thus, when looking to map the history of art and science, we are presented with more questions than answers.

Early Art History And The Renaissance

However, to attribute a date to the introduction of science to the history of art is a much more manageable task. From the beginning of the history of art up until the late 1800s, many artists focused on replicating our natural world. The principles of science, introduced by the work of theorists such as Leon Battista Alberti, created a method by which artists could perform this task. Rules such as proportion, light, and perspective gave artists boundaries for reconstructing our environment.

As Alberti explains in his treatise, On Painting, “Painting is divided into three parts; these divisions we have taken from nature. First, in seeing a thing, we say it occupies a place. Then, looking at it again, we understand that several planes of the observed body belong together. Finally, we determine more clearly the colors and qualities of the planes. Therefore, painting is composed of circumscription, composition, and reception of light.” Alberti, a prolific writer during the Renaissance, dictated with science a means for accurate natural representation, the result of which took art from stiff and disproportionate pieces such as Cimabue’s Maestà di Santa Trinita to balanced, realistic artworks such as Botticelli’s Primavera. Paintings became windows into other worlds and sculptures transformed into living beings with the help of science.

Primavera, Sandro Botticelli, 1482 | Source: Wikimedia Commons

Looking Within The 20th Century

In the 20th century, science took on a different role within art. Due to the invention of photography in the 19th century, the artistic need to recreate our natural world diminished, freeing up an opportunity to focus on ideas and the self. As artists became less concerned with natural representation and more concerned with conveying feelings or ideas, they turned to science for research regarding mental rather than physical matters.

Surrealist artists, for example, focused on revealing the unconscious in their work, a direct reaction to Freud’s arguments on psychology. Einstein’s general theory of relativity, which posits that there is a kind of space-time fabric within which planets and stars are woven, influenced our perception of time, motion, and space, the impact of which can be seen in the shattered perspectives of Cubist art. Conceptual artists such as Jenny Holzer and Sol LeWitt eschewed images with which we are familiar in favor of thought provoking statements and sculptures, prioritizing concepts over aestheticism. Artists enjoyed some of the most significant scientific events during the 20th century, and the art they created mirrored this dynamism.

Today, science is a part of our daily lives in a way that it has never been before. We are faced with science every time we search the web. Our mobile phones have become our extra limbs, without which we would not know how to function. Because we have now become closer to science through technology, the relationship between art and science must change once again.

After Technology

The modern relationship between science and art takes on many different shapes and sizes. The most obvious form of this connection is digital art. Over the past two and a half decades, some of the world’s largest museums have celebrated the world of digital art. The Whitney Museum launched artport in 2002, a hub for online commissions and new media artworks, and the Guggenheim launched its first online exhibition in 2015, titled Azone Futures Market.

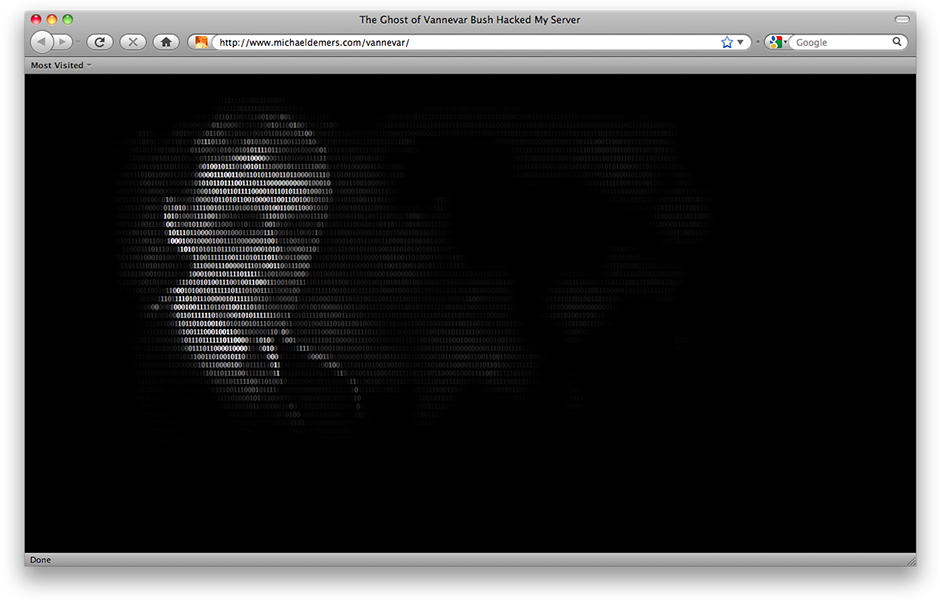

Artists such as Philip David Stearns, JODI, Sara Lundy, Andy Lomas, and Michael Demers, manipulate and play with technology to create artistic dysfunction. For example, in Demers’ The Ghost of Vannevar Bush Hacked My Server, he manages to take away the typical function of an internet browser, to provide information, and replace it with a kind of eerie game. Pieces like Phillip David Stearns’ Digital Nomads 001 show us that the technology we rely upon so heavily can be melded and morphed like clay for a sculpture. Technology provides a new material with which artists can play and dream.

The Ghost of Vannevar Bush Hacked My Server, Michael Demers | Source: Rhizome

A Digital Media Landscape

Outside of digital media, data has also served to inspire artworks. Data visualization expert Aaron Koblin creates masterpieces of color and light which demonstrate facts and data. Artist Laurie Frick, likewise, uses materials like cloth and leather to represent data sets. Her work, Time Blocks, shows a data set related to time via blocks of wood and color. The artists Giorgia Lupi and Stefanie Posavec, whose work was recently acquired by the Museum of Modern Art, spent a full year mailing data visualizations about their personal lives on postcards, achieving a beautiful collection of artworks. Data visualization art speaks about the information age in a different way than digital art does, but the message is the same. Both data visualization and digital art show how technology and science are now inseparable from our lives.

Time Blocks, Laurie Frick | Source: Visual News

A Scientist’s Approach To Art

In reaction to technology, some artists are taking an even more literal approach to expressing the growing link between science and art. BioArt, or art that uses biology as inspiration, is a method by which artists can address the link between science and art directly. Anicka Yi, in her 2017 show at the Guggenheim, Life is Cheap, explored with a team of molecular biologists and forensic chemists, the world of Petri dishes and bacteria. In the exhibition, Yi displayed strains of bacteria gathered from Chinatown and Koreatown in Manhattan and placed them on tiles to grow within a diorama. Artist Suzanne Anker, a pioneer in the bio art field, who was also one of our judges for The Chelsea International Fine Art Competition, draws similar inspiration for her works. Anker’s Biota pulls objects from the sea and places them on display, calling attention to the beauty of our natural world.

Without the growth of technology, bio art may not have received any attention, but the renewed combination of art and science spurs a renewed interest in bio art, as well.

Biota, Suzanne Anker | Source: Digital Art Archive

The history of art and science is long and nearly impossible to capture. But the impact science has had on art can clearly be traced from the Renaissance to our modern day. Technology has made it more difficult than ever to ignore science, and art has responded to this phenomena accordingly. Art gives us some sort of reprieve from technology, using its shapes and forms in order to show us that tech is no different from any other medium. As with painting and sculpture, digital art, data visualization art, and bio art, illuminate a society’s developments, forcing us to learn more about ourselves as a species.

"Ghosts" Featured in Visual Communication Quarterly

Images and text from the Ghosts series was featured in the January-March 2017 issue of Visual Communication Quaterly. Says the Editor-in-Chief:

In the Portfolio section, I present Michael Demers' series, Ghosts. Demers' interest in capturing the ephemeral is to provide evidence -- not of the real,

but instead "of the idea of documenting the act of believing." This work is a documentation that triggers memories made by the image's original photographer and its current viewers.

It alludes to the power embedded in snapshots and present a re-vision of image content curated online.

Fundamentos da Linguagem Visual.

Adriana Vaz and Rossano Silva, editors. Editoria Intersaberes (2017)

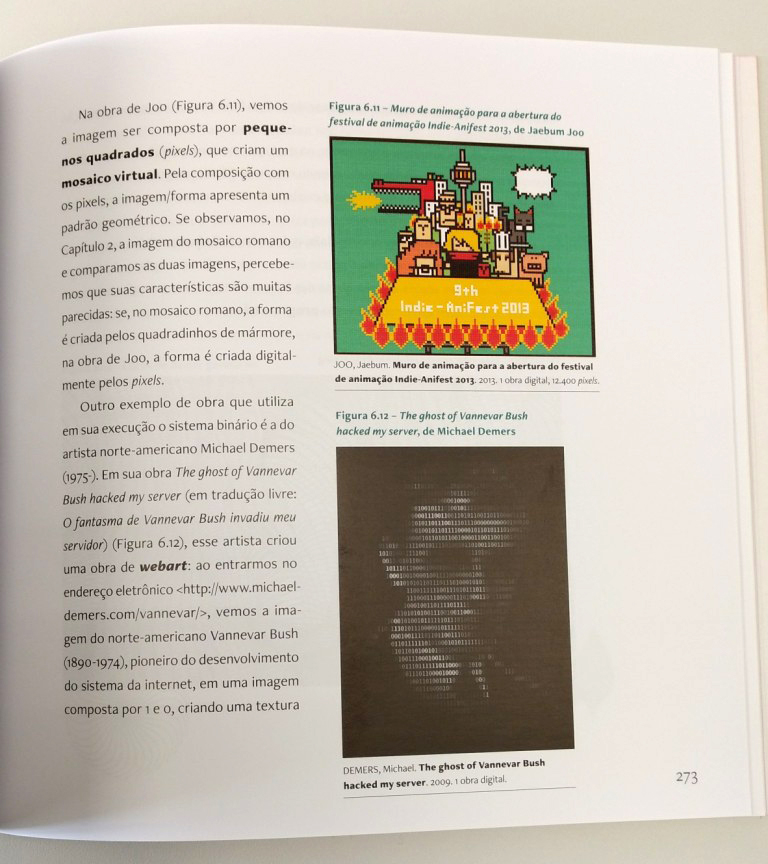

The Ghost of Vannevar Bush Hacked My Server included in Fundamentos da Linguagem Visual

From Editoria Intersaberes:

To better understand the language present in the manifold manifestations of the visual arts, we need to know the formal elements that make it up. Thus, we structure an analysis of the presence of these elements in the image and also of the interrelation that they establish in different historical,

geographic and social contexts. In undertaking this study, you will embark on an exercise that purports to investigate much more than the point, line,

plane, shape, texture, color, volume, and perspective. Reflect critically on what we call the grammar of visual language.

The Ghost of Vannevar Bush Hacked My Server

by Dido Anna

http://artelectronicmedia.com/

As a starting point of this artwork, artist Michael Demers takes the famous engineer Vannevar Bush. Bush, born in 1890, is in this context specially known for his work on analog computing and the idea of the Memex. The Memex was a (proto)hypertext computer system that individuals could use to administer their self-contained library. It follows associative trails or links that are created by the individual. The Memex is ‘a sort of mechanized private file and library’ (1). Important to point out is that the Memex influenced the development of the hypertext, which had been defined as the ‘underlying concept defining the stucture of the World Wide Web’ (2).

The Ghost of Vannevar Bush Hacked My Server can be considered a work of net.art. ‘Net.art is a self-defining term created by a malfunctioning piece of software, originally used to describe an art and communication activity on the internet. Net.artists sought to break down autonomous disciplines and outmoded classifications imposed upon various activists practices.’ (3) As a part of the New Media Exhibition ‘Zeros+Ones: The Digital Era’, Demers made a website incorporating Vannevar Bush's face, consisting of 0s and 1s, an homage to the engineer's visionary influence on the computer and the Internet. Bush's face appears and then suddenly disappears, leaving the website not only looking hacked but also frozen and unable to use.

‘On October 28, 2009 an image appeared to flash on a web server. Comprised of 0s and 1s (binary code -- the elemental language of computers), the image closely resembled that of Vannevar Bush. The code from that page was copied and pasted into a blank page, effectively “capturing” this ghost of Vannevar Bush. He appears at random, having hacked my server he now haunts it for all of eternity...’(4)

I would like to refer to the artworks of Jodi.org, who make Web-based artworks that uses the medium's vernacular as the content of their works. When accessing their website wwwwwwwww.jodi.org, it appears at first to consist of meaningless text, until you have a look at the HTML source code which reveals detailed diagrams of hydrogen and uranium bombs. The website reflects the Borgesian non-lineair approach to writing HTML. The artists play with the famous texts of Vannevar Bush and Luis Borges, because both authors 'have the idea of a massive branching structure as a better way to organize data and to represent human experience'(5).

1. Vannevar Bush, ‘As We May Think’, 1945.

2. Natalie Bookchin, Alexei Shulgin, Art and Electronic Media, p. 240

3. www.wikipedia.com

4. www.michaeldemers.com

5. Lev Manovich, 2003.

http://www.michaeldemers.com/vannevar/

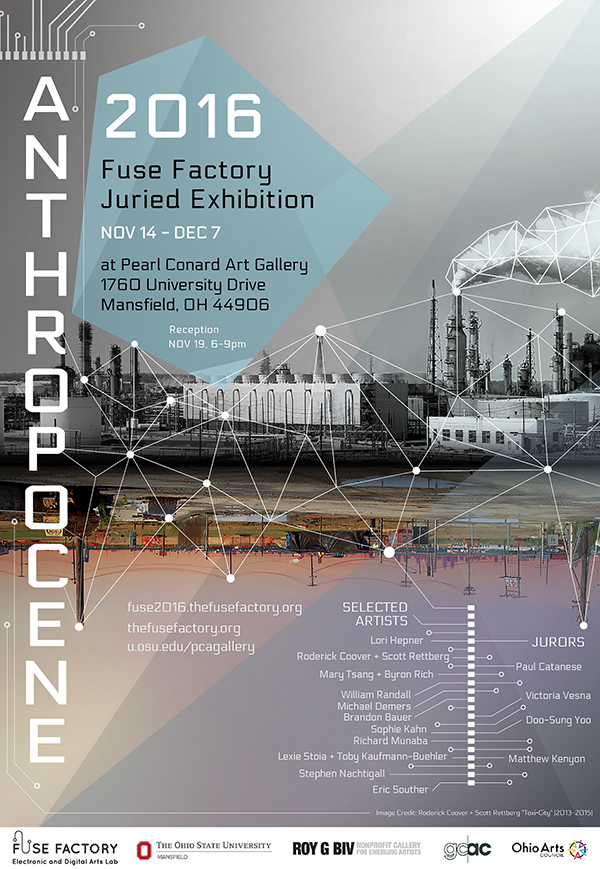

“Anthropocene” Fuse Factory at the Pearl Conard Art Gallery, Ohio State University

"The Sky is Falling (A Day in the Life...)" included in "Anthropocene"

"Since the start of the current epoch – the Holocene – humans have been physically transforming the natural world and, in the process, technologizing nature’s

inhabitants and environments to benefit human needs and desires. The human activity engendered by this anthropocentric mindset, while benefiting human health and

well-being in a myriad of ways, has also negatively affected a wide range of ecosystems, resulting in ecological destruction, extinction, genetic malformations and abnormalities,

and other problematic environmental phenomena. As a result, some scientists have proposed that we are entering a new geological epoch: the Anthropocene,

an epoch characterized by the global changes wrought by human actions made possible by technology’s evolution."

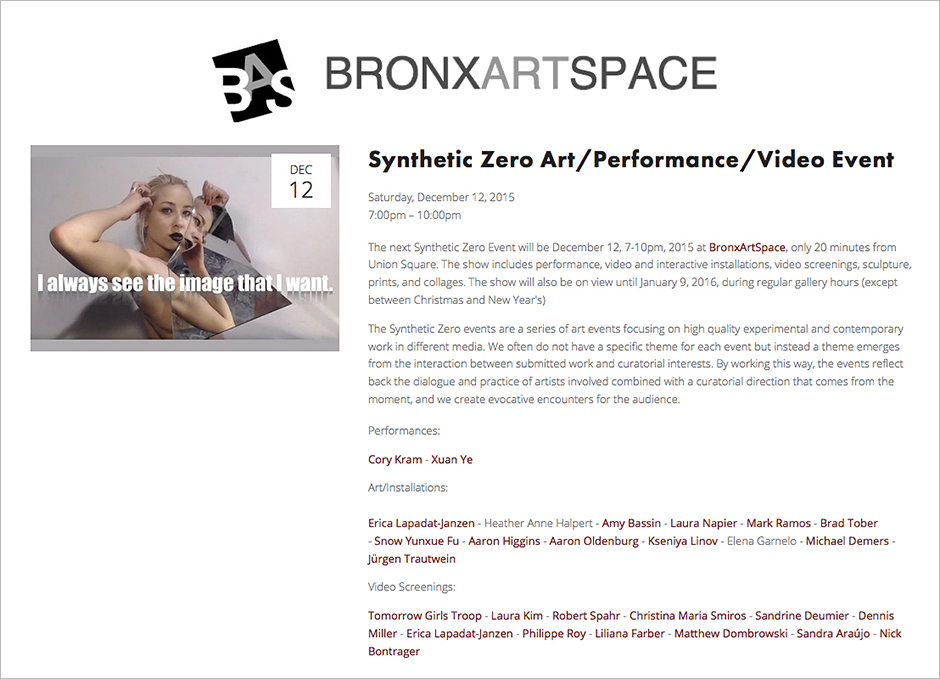

Bronx Art Space

"Wallpaper" included in the exhibition "Synthetic Zero"

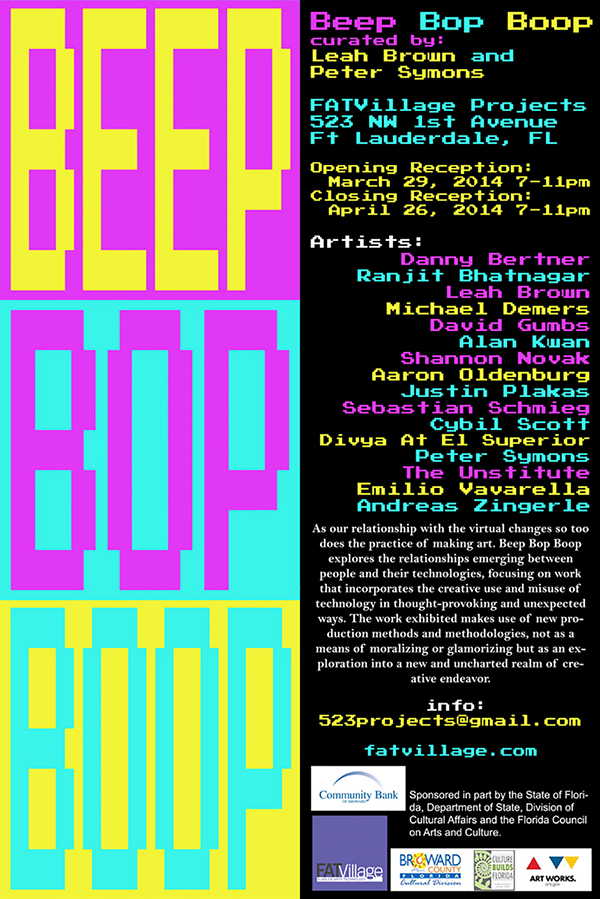

“Beep Bop Boop” at the FATVillage Projects

"The Sky is Falling (A Day in the Life...)" featured at FATVillage Projects

“COLLISION20″ Catalog Available for Download

Download the catalog for the COLLISION20 juried exhibition taking place at the Boston Cyberarts Gallery between January 17 and February 23, 2014.

One of my more recent lo-tech prints, low_resolution_wormhole, was selected for exhibition.

Works Included In “The Wrong – Digital Art Biennale”

Three of my new media works have been accepted into The Wrong – Digital Art Biennale: Homeostasis Lab: The Ghost of Vannevar Bush Hacked My Server; Color Field Paintings (Browser); and The Sky Is Falling (A Day in the Life…).

From "The Wrong" website:

“Homeostasis Lab has been created in Sao Paulo by the Composting Curators: Julia Borges Araña and Guilherme Brandão in the context of The Wrong Digital Art Biennale being a

pavilion that receives unlimited submissions from around the world.”

Foundations of Digital Art and Design

Foundations of Digital Art and Design is now available from Pearson/New Riders.

I contributed to the chapter on Revision Practices in Media Art and Design, where I discuss my work The Sky Is Falling (A Day in the Life).

From Pearson:

All students of digital design and production–whether learning in a classroom or on their own–need to understand the basic principles of design.

These principles are often excluded from books that teach software. Foundations of Digital Art and Design with the Adobe Creative Cloud reinvigorates software training

by integrating design exercises into tutorials fusing design fundamentals and core Adobe Creative Cloud skills. The result is a comprehensive design learning experience.

Interviews with or essay contributions by Pencilbox Studios, riCardo Crespo, Michael Demers, The League of Imaginary Scientists, and Jovenville.

Book Review of “Net Works” in Visual Communication Quarterly

A review of Net Works: Case Studies in Web Art and Design has been written by Karie Hollerback for the April-June 2013 issue of Visual Communication Quarterly.

Click here to read the PDF. I contributed to Chapter 1: Formalism and Conceptual Art, where I discuss my work Color Field Paintings (Browser).

Future Learning Spaces: Conference Proceedings

The Sky Is Falling: A Day in the Life was featured as part of the Future Learning Spaces conference at Aalto University in Helsinki, Finland last November.

The conference proceedings have recently been published and are available as a free download from Aalto Press.

Net Works: Case Studies in Web Art and Design

Net Works: Case Studies in Web Art and Design is now available from Routledge Press.

I contributed to Chapter 1: Formalism and Conceptual Art, where I discuss my work Color Field Paintings (Browser).

From Routledge:

Net Works offers an inside look into the process of successfully developing thoughtful, innovative digital media. In many practice-based art texts and classrooms, technology is divorced from the socio-political concerns of those using it. Although there are many resources for media theorists, practice-based students sometimes find it difficult to engage with a text that fails to relate theoretical concerns to the act of creating. Net Works strives to fill that gap.

Using websites as case studies, each chapter introduces a different style of web project–from formalist play to social activism to data visualization–and then includes the artists’ or entrepreneurs’ reflections on the particular challenges and outcomes of developing that web project. Scholarly introductions to each section apply a theoretical frame for the projects. A companion website offers further resources for hands-on learning.

Combining practical skills for web authoring with critical perspectives on the web, Net Works is ideal for courses in new media design, art, communication, critical studies, media and technology, or popular digital/internet culture.